I hate stock buybacks. I think they are one of the most self-serving things that corporate America does. Instead of investing in workers and in training and in research and in equipment, they don’t do a thing to make their company better and they artificially raise the stock price by just reducing the number of shares. They’re despicable. I’d like to abolish them.

—Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer August, 2022

A Boeing whistleblower is testifying before Congress today that the 787 has dangerous flaws in the way it’s put together.

Senator Richard Blumenthal, who chairs the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee’s investigations subcommittee that will hear from the whistleblower, told The New York Times he has heard:

“Repeated, shocking allegations about Boeing’s manufacturing failings [that] point to an appalling absence of safety culture and practices — where profit is prioritized over everything else.”

Profit?

The last year that Boeing invested in creating a new jet airplane from scratch was 2004. While it costs around $7 billion to develop a new plane, Boeing chose to save that money by “upgrading” their 737 line to the infamous 737MAX, which has now killed hundreds of people.

But just between 2014 and last year, Boeing showed a profit of over $95 billion. If they didn’t spend that money on improved safety, new products, or paying their workers better, where did it go? Follow along…

Just as an example, let’s say you and I owned a publicly traded corporation with 100 shares that sold for $100 each (yes, it’s a very small corporation!). You own ten shares ($1,000 worth of stock), I own ten shares (ditto), and the general public owns 80 shares. The notional stock value of the company is 100 shares times $100 each, or $10,000.

So, how do you and I increase the value of our stock so we can sell some or all of it (or borrow against it) for a profit?

The way businesses have traditionally increased the value of their shares — all the way back to the invention of the modern corporation when Queen Elizabeth I chartered the East India Company on December 31, 1600 — has been to grow the company.

Develop new products. Build new airplanes or widgets. Open new stores. Invest in a sales-force or advertising campaign. Expand manufacturing capability and/or open new factories. Improve employee productivity and retention with better pay and benefits.

But what if there was a way to make our stock price go up without any real work on our parts? No need to develop new products, open new outlets, increase worker pay, or sell a single extra widget?

Turns out, there is. All we have to do is take some of the company’s profit this year into the public marketplace (the stock exchange we’re listed on) and “buy back” from the public, say, 20 shares for $100 each and “retire” or, essentially, destroy them.

Instead of 100 shares, our company now only has 80 shares, but it’s still worth $10,000. Which means each share magically went from a price of $100 to a price of $125! ($10,000 divided by 80 = $125 per share.)

The value of your and my investment in our company each went from $1,000 to $1,250 without either of us having done anything other than executing that stock buyback: if we sold our stock today we’d show an instant profit of $250 each. All our other stockholders are happy, too, because their stock also went up in price.

Back in 1934 when, in the wake of the epic stock market crash of 1929 caused by insider trading, President Franklin Roosevelt created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and put Joe Kennedy in charge of it, one of Kennedy’s first actions was to largely outlaw these kinds of stock buybacks, labeling them “stock price manipulation.”

(My late friend Gloria Swanson, who knew both Kennedy and FDR well, told me over dinner in her New York apartment in the early 1980s that FDR told her he appointed Kennedy head of the SEC because, she said, imitating FDR’s voice, “It takes a crook to catch a crook.”)

Thus, from 1934 until the Reagan Revolution, American businesses grew the value of their stock by growing the value of their companies. It made America the leader in industrial manufacturing, innovation, and R&D. Sam Walton started Walmart with the slogan, hung as giant banners over his stores and echoed as the title of his autobiography, “100% Made in the USA.”

With that innovation and business expansion, we developed lifesaving new drugs, the transistor and integrated circuit, put men on the moon, and produced more patents than every other country in the world combined.

Today, though, we’ve lost that distinction: China produces more patents than the US and it takes massive government subsidies to get companies to develop new products like chips or electric cars.

Boeing, instead of building new airplanes to expand and upgrade their fleet, spent over $60 billion on stock buybacks in the years leading up to the 2019 grounding of their MAX fleet. Just between 2013 and 2019 they bought back an astonishing $43.5 billion in shares.

Not one penny of that money did anything to increase the value of Boeing: instead, it simply manipulated upward the price of their stock, as the purchased and retired shares vanished from the marketplace per the example I opened this article with.

Because most of the company’s senior executives got most of their compensation in stock rather than pay (to avoid the corporate loss of tax deductibility on salaries over $1 million), the benefit went primarily to Boeing’s executives and stockholders. Regular salaried and hourly employees were left out of the equation altogether, as was much of the ability to grow the company.

In fact, to free up money to pay for stock buybacks to feather the nests of the company’s senior executives and shareholders, the company restrained pay increases for regular employees, cut back on quality control employees, and created the kludge of the jerry-rigged 737MAX 8 and 9 planes.

According to data compiled by William Lazonick and the Academic-Industry Research Network from Boeing’s 10-K SEC filings, in the 20 years from 1998 to 2018 the company bought back $61 billion worth of stock, representing 81.8 percent of all profits. When you add the dividends paid to shareholders during that same period, the amount was 121 percent of its profits.

In other words, the senior executives appear to have spent the past few decades looting the company for their own benefit.

And Boeing isn’t alone in this: virtually every American exchange-listed company is doing the same, which is a main reason why American worker pay and innovation have both been so stagnant for so long.

Apple, for example, has bought back $467 billion in their own shares since 2012, rather than invest in manufacturing facilities and decent worker pay here in the US. Facebook bought back over $50 billion of their own stock just in 2021, while laying off people responsible for keeping the platform safe, making Mark Zuckerberg the richest millennial in America, controlling over 1/50th of all millennial wealth.

In the nine years leading up to 2021, the S&P500’s 474 corporations spent $5.7 trillion buying back their own stock: that’s more than half their total income. Further gutting their ability to pay their employees well or develop new products, they paid another $4.2 trillion in dividends to shareholders, representing 41 percent of their net income.

And the problem is equally pervasive among companies listed on the Dow and the NASDAQ.

How did it come to this?

It started with Reagan’s putting John Shad— the Vice Chairman of the monster investment house E.F. Hutton — in charge of the SEC, which regulates monster investment houses.

Shad wasted no time in deregulating stock buybacks, instituting in 1982 what’s now known as “Rule 10b-18” that made stock buybacks explicitly legal for the first time since 1934.

Since then, share buybacks have become the most personally profitable business scam CEOs and senior executives can run against their own employees, companies, and communities.

When Reagan and Shad made this change in 1982, the average compensation of CEOs was around 30 times that of their average employee. CEO’s often lived in the same communities as their workers, or in a just slightly more upscale part of town.

Today CEO compensation is between 254 and 10,000 times the average employee, depending on the industry, and CEOs live in palatial estates with servants’ quarters, yachts, and private jets; most of that increase in their annual income is the result of their companies’ repeatedly executing stock buybacks over the past 40 years.

Corporate CEOs call this “maximizing shareholder value” and claim it’s how capitalism is supposed to work. But Adam Smith never anticipated such a thing, would have called it a scam, and he would have been right.

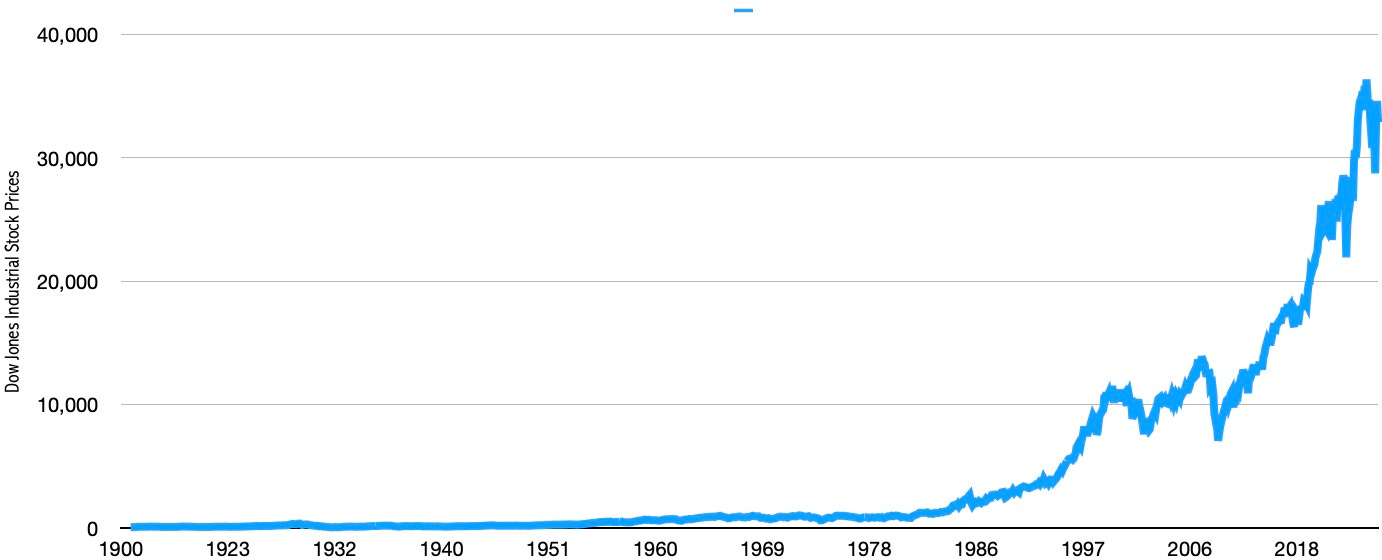

As more and more CEOs got in on the hustle since Reagan legalized it in the 1980s, it’s come to account for much of the 40-year explosion in the price of publicly traded stocks.

Investors don’t complain because they’re making out well, too (and 84 percent of all stock in America is owned by the top 10 percent).

After all, why spend money on improving the company — or even on routine maintenance and safety — when you can personally cash in just as effectively by simply using your company’s revenues to engineer a new stock buyback scheme every year?

As William Lazonick wrote for The Hill in 2018:

“Most recently, from 2007 through 2016, stock repurchases by 461 companies listed on the S&P 500 totaled $4 trillion, equal to 54 percent of profits. … Indeed, top corporate executives are often willing to incur debt, lay off employees, cut wages, sell assets, and eat into cash reserves to ‘maximize shareholder value.’”

It’s all done, Lazonick notes, to facilitate share buybacks.

Senators Bernie Sanders, Chuck Schumer, Elizabeth Warren, and Tammy Baldwin have all written about this, decrying stock buybacks and offering specific proposals to tax or even outlaw them. (Biden put a 1% tax on them with the Inflation Reduction Act, a breakthrough, but it should probably be at least 40% to have any impact.)

It’s time to declare the 43-year Reagan Revolution’s neoliberal experiment a failure, and outlaw or heavily tax the share buybacks that are one of its most visible markers. Joe Kennedy knew what he was talking about when he criminalized them, even if he was a crook.